“Thus for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem — how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.” – John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes

Almost 100 years ago, in 1930, the economist John Maynard Keynes estimated that his grandkids would work just 15 hours per week, with machines taking care of most tasks. So, how are we doing John? Where is my promised utopia of abundant leisure?

Because whilst I want to be optimistic about ChatGPT and Midjourney, we don’t have a great historical precedent when it comes to this sort of thing…

100 years of progress

From the plough to the computer processor, technological advances have revolutionised how we work, and the rate of revolution has only increased. As Kurzweil put it: “Technological change is exponential. We won’t experience 100 years of progress in the 21st century—it will be more like 20,000 years of progress (at today’s rate).”

Let’s take a look at some of the huge technological advancements of the past century which have shifted the paradigm of work.

- Assembly line production: Developed by Henry Ford in the early 20th century, assembly line production involved breaking down the production process into smaller, simpler tasks that could be performed by specialised workers. This method increased efficiency and productivity and allowed for mass production of goods such as automobiles. Ford famously introduced the 2-day weekend and the 40-hour work week. A class move from Henry back in 1920.

- Computerisation: The widespread use of computers have enabled businesses to automate tasks, store and analyse vast quantities of data, and communicate more efficiently.

- Industrial robotics: The development of industrial robots that can autonomously perform complex tasks such as assembly, painting, welding has made manufacturing significantly more efficient and effective.

- Information technology: Information technology has rapidly advanced with the development of the internet, mobile devices and cloud computing creating entirely new industries around it and disrupting old ones.

- Artificial intelligence: Artificial intelligence and machine learning involve the use of computer algorithms to analyse data, recognise patterns, make decisions and produce new outputs.

With all these advances, you might expect us to be close to John’s dream. But most people still work the same 5-day, 40-hour week introduced 100 years ago and many dream of just doing a Dolly Parton 9 to 5.

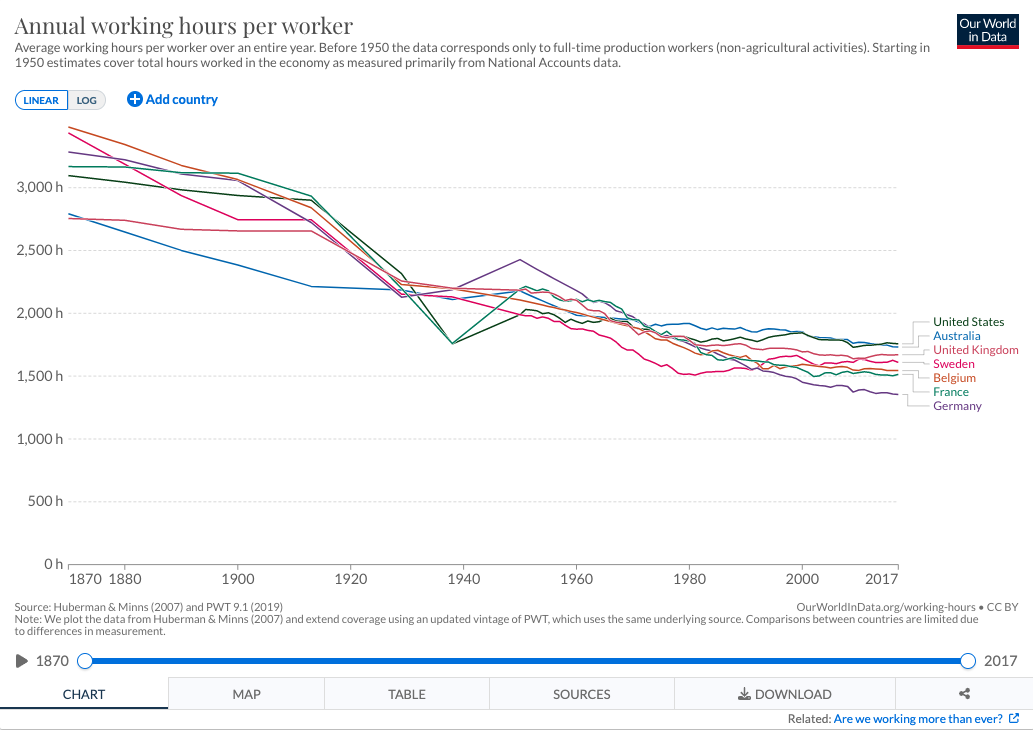

It’s worth noting that we’re definitely working less than our ancestors in 1870 (thank you?) but I’d have hoped that working hours would have decreased proportional to the rate of technological increase since then. As you can see from the chart, what starts off as a sizeable gain becomes pretty much horizontal by the end for some countries.

The benefits of progress

Now I don’t want you to think I’m a Luddite. There are enormous benefits to progress outside of how it impacts our working life. The team at Our World In Data do a wonderful job of showing reasons to be optimistic about the progress we’ve made. Global literacy rates have increased from 12% in 1800 to almost 86%, life expectancy has more than doubled, child mortality has halved in less than three decades. Improvements in medicine, sanitation, education are all a result of technological progress. Many countries have pulled themselves out of poverty and people globally have a better standard of living.

So I’m not saying that we shouldn’t make progress simply because we will lose jobs. I’m trying to argue that in ‘Advanced Economies’ we need to have a better conversation about what we want from all this progress when it comes to work.

As far as I can tell, most of the conversation around technological displacement seems to be focused on two points:

1) Don’t worry, technology creates more jobs than it destroys

2) It’s good for the economy

The World Economic Forum says we shouldn’t fear AI as it will create job growth. But is this the best we can hope for?

The benefits of progress… aren’t evenly distributed

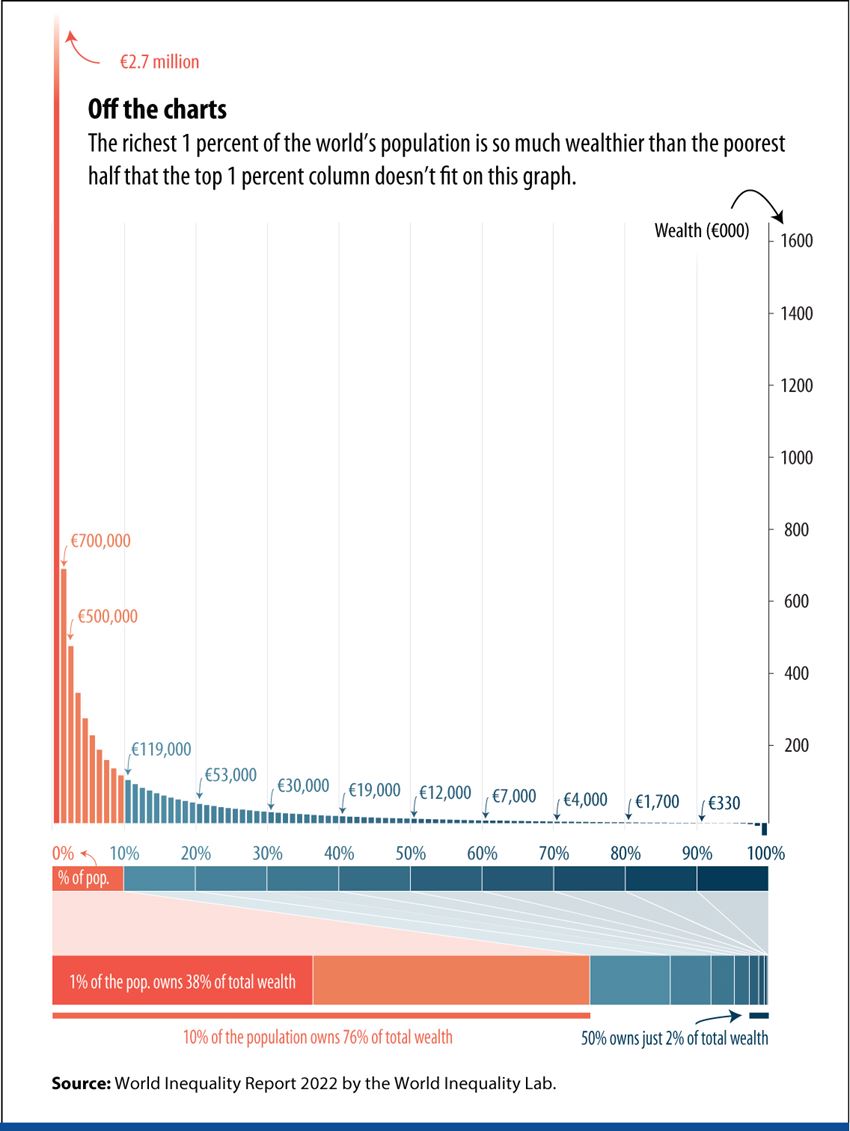

So if the benefits of automation aren’t being passed to the labourer (who is doing the same amount of work as 100 years ago if they haven’t lost their job), who is benefiting? Well it’s a fairly obvious answer…

A few people are benefiting enormously!

Income inequality has risen dramatically. The top 1% owns 38% of global wealth. The top 10% own 76% of total global wealth.

In the US, in 50 years, the share of national income earned by the top 10% of earners in the US has increased from ~30% to ~48%. That’s almost half of the US’ national income going to just 10% of the population.

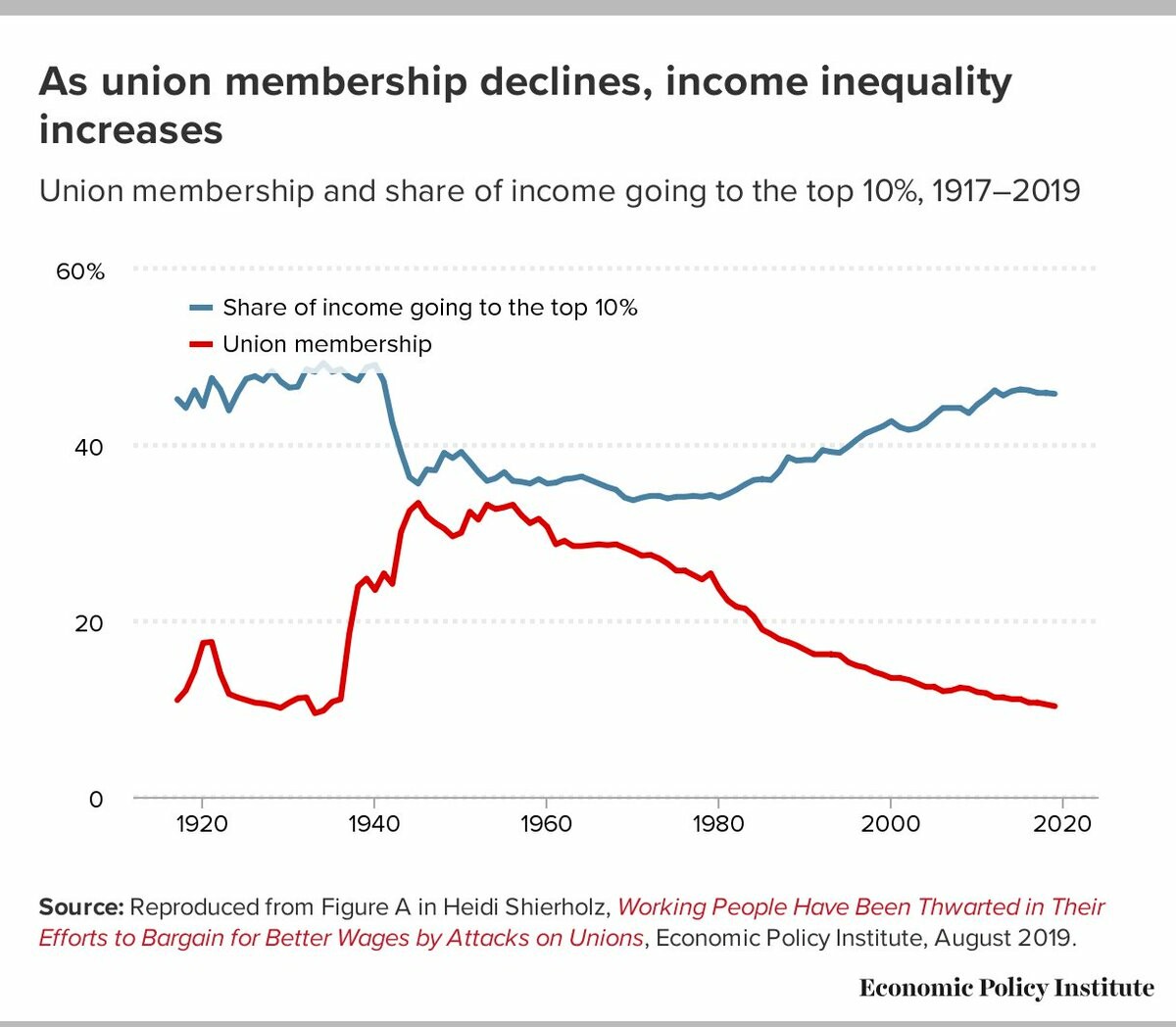

Interesting that income inequality also correlates with a decline in unions 🤔

The rest are working longer for less

Automation promises economic growth, and yet many incomes are not growing to match. For those born in the 1940s and 1950s, incomes would typically double from their late 20s to their early 50s. However, those born in the 1960s only saw income grow by around 50% over that period, whilst those born more recently look set to see weaker growth still as they age. This means it’s harder to save one’s way up the wealth distribution.

One result of this is unattainable house prices. The average house in the UK currently costs around nine-times average earnings. The last time house prices were this expensive relative to average earnings was in the year 1876, nearly 150 years ago.

Over a third of Americans don’t believe they’ll ever retire. And according to the Boston College Center for Retirement Research (CRR), half of US households will not have enough income to maintain their standard of living in retirement even if they work to age 65 and annuitize all financial assets, including securing a reverse mortgage on their home (if they even own a home).

Younger generations are seeing the touted benefits of capitalism disappearing. No wonder they’re pissed. And I’m sorry if you also feel depressed reading this. This is how many people feel at work right now.

There must be a better way to do business

We’ve seen positive momentum recently. Cultural attitudes have shifted creating better working conditions. For example, there’s been a huge shift when it comes to skilled labour desiring a sense of purpose in their work, demanding better working conditions, opting out of discretionary effort and hustle culture. Many people in white collar work have much more flexibility than they did only a few years ago. Companies had to adapt if they wanted to retain and attract talent.

With that being said let’s be real here, most companies have only listened because they still need that workforce. Soon they won’t. (Remember when only a few years ago every Think Tank’s prediction on AI was that creative jobs would be the last to go, if ever? Now every graphic designer is worried about Midjourney and even the lawyers are anxious about ChatGPT.)

Personally I do think there is hope, but we have to start having important conversations now in order to design the world of work we need.

We’re starting to have conversations about a 4-day week and some brave businesses are trialling it. And I do genuinely mean brave. It has taken us 100 years to fight for an extra day off because of how deeply ingrained the systems of belief are that perpetuate our current economic system.

We need to start talking about our worth as individuals as being separate to our utility and productiveness – and certainly separate to our salary.

We need to start talking about introducing a robot tax and a Universal Basic Income.

We need to vote for policies that levy appropriate taxes on individuals and corporations.

We need to start setting up B-Corps and Social Impact Businesses so that shareholder value isn’t valued above all else.

We need to support our workers who want to unionise and we need to support our workers who strike.

And we need these to be conversations that everyone is engaged in from the intern up to the CEO.